You are here

Drawing Conclusions: The Art of Forests over Time

Think of your favorite tree. Is it a sprawling red oak, dominating the landscape? Perhaps it is an elegant quaking aspen, shaking in the summer breeze. Can you tell me how old it is? Can you tell me the history of the surrounding trees and the land? Can you say how it will look in 10 years? 50 years? 250 years? Difficult as it may seem, there are researchers here at the Harvard Forest asking these very questions, and the answers are never as straightforward as you’d think. Hurricanes, disease, insects, farming, frosts, drought, logging, tornadoes, and other types of disturbance shape and transform the landscape over vast periods of time, resulting in the forests that we know and love today, and forming the forests of tomorrow.

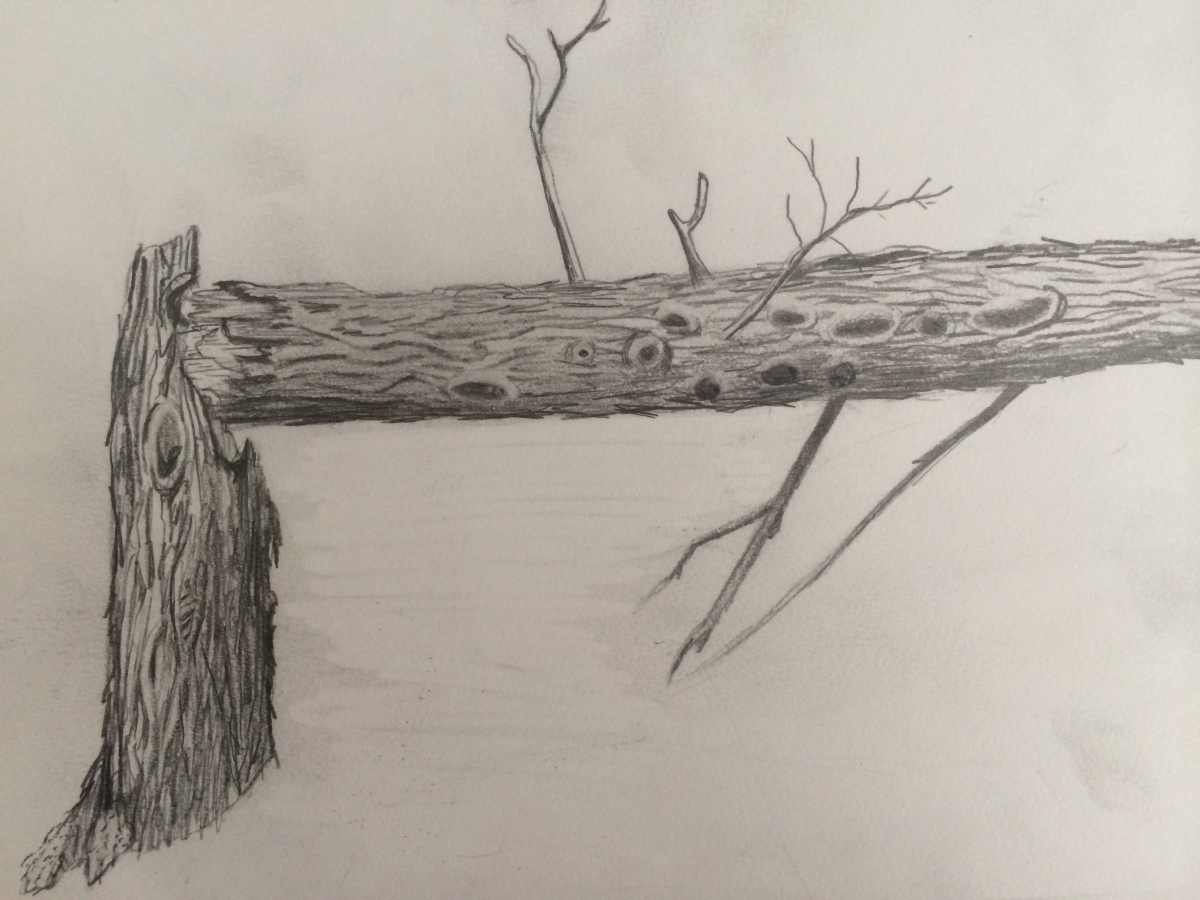

Like us, trees have a memory, and it is etched into their very being. Look up a 250 year old tree. See the bark pattern changing, and you can see how fast the tree grew at different points in its life. The twisting, sinuous branches are a sign of old age. Healed injury and infection are apparent in the imperfect knots and scars. For the full story, we must get to the core, literally. The tree’s rings tell its history, year to year, from its exact age to an entire record of disturbance to the condition of the surrounding land.

Like us, trees have a memory, and it is etched into their very being. Look up a 250 year old tree. See the bark pattern changing, and you can see how fast the tree grew at different points in its life. The twisting, sinuous branches are a sign of old age. Healed injury and infection are apparent in the imperfect knots and scars. For the full story, we must get to the core, literally. The tree’s rings tell its history, year to year, from its exact age to an entire record of disturbance to the condition of the surrounding land.

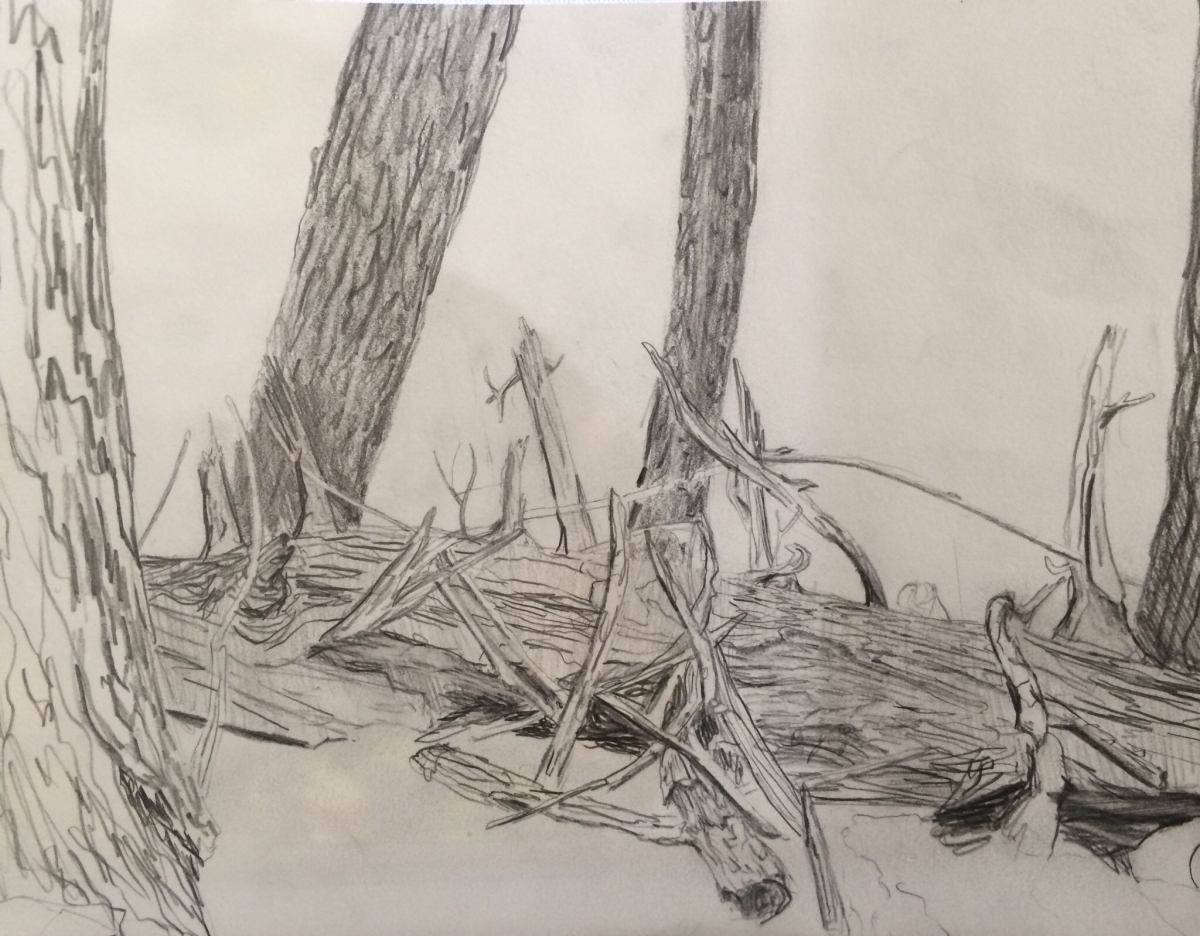

While rings provide a polished snapshot of a tree’s life, it is difficult for people to conceptualize the lifespan of a single tree, of a forest, of a landscape. Can you imagine growing and changing for hundreds, maybe thousands of years? Many people assume that a forest will look the same in 100 years as it does today, that their favorite tree will always be there, but this is likely not the case. Forests are dynamic, their condition constantly, though often subtly, shifting. I challenge you to go out and take a picture of your favorite tree, of a forest, or a landscape today. Then, make an effort to revisit in just 10 years, and see how much has changed. Bonus points if you can see how much you have changed.

My project this summer aims to examine the relationships between people, trees and the forest, and time. With the guidance of my fabulous mentors, Clarisse Hart and Neil Pederson, I will capture stages of physical and personal development in both people and nature through illustration and writing. By making forest time relative to human time, I aim to have people use their personal thoughts and experiences to inform their understanding of forest dynamics and development. Conversely, it is my hope that people will use the perspectives of trees and the forest to gain a greater understanding of themselves and their relationship with time.

While my project is a little different than most, with a much greater emphasis on humanities and communication, it has allowed me a unique breadth of experiences. I have traversed old growth and cored tree rings with Neil and David Orwig, examined pulled down trees with Audrey Barker-Plotkin, visited fine arts museums with Clarisse, taken sediment samples from a pond with David Foster and Wyatt Oswald, spoken to Dave Kittredge about land-owner decision making, and met many more fascinating and inspiring people, all working towards a common goal of understanding and preserving the landscapes that humans both cherish and require. My goal is to take all of that information, care, and enthusiasm, and make it interesting and accessible for everyone. The communication of scientific concepts for the public is integral to the work that the researchers at Harvard Forest are doing, and I am honored and excited to be that translator. Though it hasn’t even been a month since I’ve arrived, I feel very much at home; the people are excellent, and the food is even better. I am eager to see how my time at the Forest shapes me.