You are here

Global climate change with ants and slugs

Ants with Matt Combs

Melting wax, digging through sand, and orchestrating the spectacular deaths of entire colonies of ants - seems more fitting for a preschooler than an undergraduate student, working a full-time job. Yet somehow, fate has landed this college senior his dream job: spending the summer in a professional scientific setting while doing things even a little kid would find cool.

I represent one-half of the Warm Ants team this summer, which is a long-term research project working to determine the effects of rising air temperatures on ant ecology. We take measurements every month from 15 different chambers, of varying heat levels. Our day-to-day agenda is always changing as we help with the workload of many different projects related to Warm Ants. Luckily, we have also been encouraged to create our own independent projects. With the support of my two mentors, Shannon Pelini and Israel del Toro, and my ever-helpful REU counterpart, Katie Davis, I have set out this summer to investigate the nest architecture of the ant Formica subsericea.

I want to discover the general shapes of these ants' nests, which has never been formally investigated with this species! I want to understand how the population size is related to the volume of the entire nest and the individual chambers. I also want to determine how the eggs, called the brood, are organized beneath the surface. The social hierarchy of a colony is decided by the way the brood is maintained during development. If we want to understand the way the colonies social structure is regulated we must start to dig deeper, literally, by observing the organization of the colony beneath the soil. We will compare our observations with the temperature gradient at different depths of the soil to see any possible relationships between nest/colony architecture and temperature.

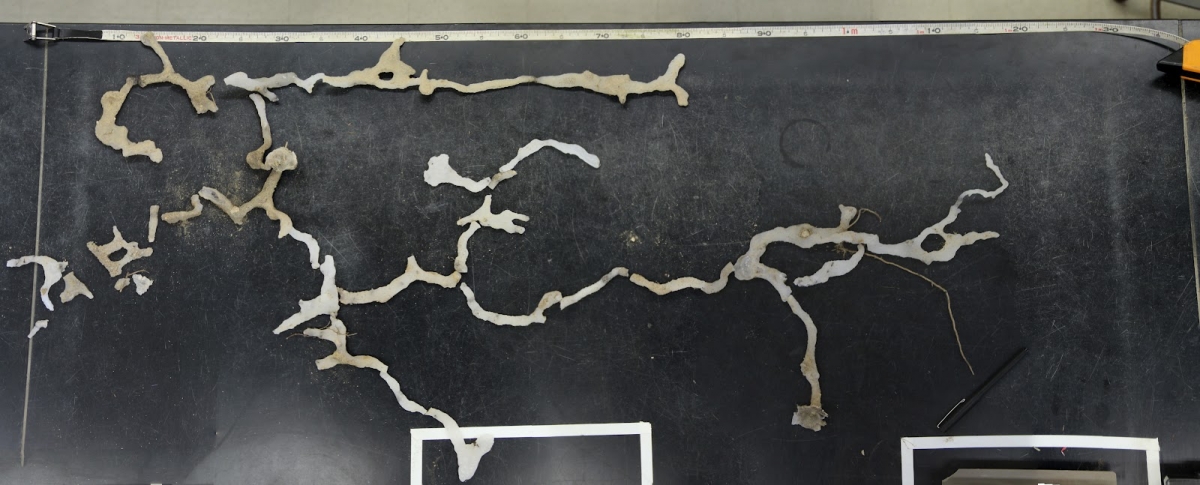

In order to understand the shape of the nest beneath the surface and also document the abundance and placement of both ants and brood within the nest, we use wax casts. We pour molten wax down the entrances of the nests, let them harden into a solid form, then dig them out–very carefully. We reassemble them in the lab to inspect the layout of the nest, then break them down piece by piece, remelting and counting the ants and eggs left in the wax.

We also take temperature readings at different levels and at different times of the day using a thermometer probe. By pouring the wax casts at different times of the day, we are essentially freezing the nests in time, and can begin to understand how the ants change the way they organize themselves and the brood throughout the day. When paired with our temperature data, this should tell us something about the way the ants react to temperature shifts.

The creative and analytical sides of this project come together in the documentation of the final nest architecture. We must be careful to record the exact position of each chunk of ant nest we pull out if we are to reassemble it accurately. In the lab I put them back together like a wild 3-D puzzle and photograph them. Even now I am still working to find the best way to document the final structure of the nest, a creative endeavor that I am excited to work through.

The nests which I dig up do not follow an obvious template. They twist and turn, rise and dip, connect and end for no obvious reason. Their designs are utterly chaotic, and can seem illogical from a distance. But of course, the architecture of F. subsericea nests allows the function of the colony as a whole, and the entire process has become a sophisticated and effective system honed by evolutionary forces. The chaos hides a pattern of productivity. The only way to fully understand these insects and their architectural products is to also embrace the less logical thought processes and creative techniques not usually required when setting up a scientific experiment. In other words, I must think like an ant.

Slugs with Katie Davis

Slugs don’t exactly have a stellar reputation. They’re slimy, and they love to eat plants that people grow in their gardens. But slugs aren’t all bad—they play important roles in ecosystems like Harvard Forest. They help to break down leaves and other material on the forest floor, making nutrients available to plants. There’s also some evidence that slugs eat and disperse plant seeds. And they’re pretty cute, especially when they have their eyestalks out!

We don’t know how slugs, and the ecosystem processes that they contribute to, will be affected by the changing climate. Because slugs dry out easily and only come out to eat when it’s cool enough (usually at night or on cloudy days), it seems likely that they will have an adverse response to warming.

This summer, with the help of my mentors, Shannon Pelini and Israel Del Toro, and my fellow student researcher Matt, I’m exploring the effect of warming on slugs and their role in decomposition of leaf litter. I collected slugs using peanut butter as bait and divided them into eight small terrariums.

Each of these will be placed in one of eight warming chambers in the forest. These are areas fenced with plastic sheeting that are heated by hot water that warms the air within the chamber. Each group of slugs will be exposed to temperatures ranging from 2-6˚ Celsius above the ambient temperature in the forest, and one group will be placed in a control chamber in which the temperature is not manipulated.

Throughout the summer, I will be monitoring how much the slugs eat and how much weight they gain or lose in order to assess how well they do in different temperatures. I will also measure the rate of decomposition in the terrariums with slugs as well as in identical terrariums without slugs to quantify the slugs’ contribution to decomposition. Finally, I will compare the rate of decomposition across the temperature gradient to see how the slugs’ role in decomposition changes with temperature. Together, all of these components will shed a bit more light on how slugs, and the ecosystem processes they contribute to, may respond to a global temperature increase.