You are here

Butterflies and bumblebees

This summer, we’re studying animal movement with Dr. Elizabeth Crone and some of her “Cronies” (lab members and affiliates): post-doctoral fellow Greg Breed, Harvard OEB graduate student James Crall, and research intern Dash Donnelly. We’re looking at how anthropogenic landscape changes and resource availability affect population dynamics in two different organisms: bumblebees and butterflies. Since we’re both especially interested in morphological changes, we’ll sometimes stop fieldwork for a day and head out to the Concord Field Station in Bedford, MA where we’ll use high-speed cameras to examine insect flight in slow motion.

Butterflies with Aubrie

![[Ahh, what a beautiful pupa! I’m studying the Baltimore Checkerspot with Greg (AKA Dr. Greg Breed AKA Butterfly Whisperer Extraordinaire AKA Best Mentor and he didn’t even pay me to say that).]](/sites/default/files/REU_McKenna1_2013.jpg)

![[Oh, there he is with Elizabeth! (AKA Dr. Elizabeth Crone AKA Fearless Leader of the Cronies). ]](/sites/default/files/REU_McKenna2_2013.jpg) The organism I’m studying this summer is the Baltimore Checkerspot, a butterfly species in the family Nymphalidae. It’s also known as Euphydryas phaeton, Latin for “The cutest little butterfly on the planet. Or at least in Massachusetts.” They haven’t emerged as butterflies this season, but they are starting to pupate.

The organism I’m studying this summer is the Baltimore Checkerspot, a butterfly species in the family Nymphalidae. It’s also known as Euphydryas phaeton, Latin for “The cutest little butterfly on the planet. Or at least in Massachusetts.” They haven’t emerged as butterflies this season, but they are starting to pupate.

My main focus of study this summer is centered on the Baltimore Checkerspot’s food when they are in their larval stages. Back in The Dark Ages, (or, before my dad was in high school) the Baltimore Checkerspot exclusively used a plant called the White Turtlehead to lay eggs and munch on. However, our Checkerspots have recently been using a "weedy" plant called the English Plantain for the same purposes as the White Turtlehead.

This is a blurry picture featuring a larva and my sparkly nail polished finger! I tried to catch another picture, but right after this was taken, Greg said “Aubrie, you’re rolling around in a big patch of Poison Ivy.” Fieldwork is cute like that.

This is a blurry picture featuring a larva and my sparkly nail polished finger! I tried to catch another picture, but right after this was taken, Greg said “Aubrie, you’re rolling around in a big patch of Poison Ivy.” Fieldwork is cute like that.Anyhow, the Plantain has become more pervasive in the Checkerspot’s habitat mainly due to anthropogenic changes in the landscape. The Checkerspots, being the pragmatic little guys they are, have started incorporating the Plantain into their life history, and have experienced somewhat of a population boom.

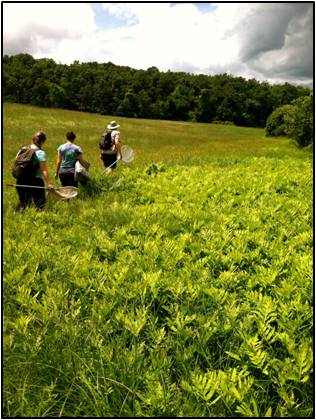

With this broadening of the Baltimore Checkerspot’s larval diet, I’ll be studying how the change in diet – Turtlehead (Chelone) versus Plantain (Plantago) -- affects the flight ability of adults. I’m going to be really busy this summer, both in the field and in the lab, but this is truly the best gig on the planet. I’m learning, I’m researching, I get to hang out with geniuses every day, and my job duties are the following:

1. Read a lot of articles about butterflies

2. Chase butterflies around meadows with a big net

3. Mark butterflies with glitter gel pens

4. Use a high speed camera to film butterfly flight

5. Repeat

I really don’t think it gets better than that (even though I'd be okay with a little less Poison Ivy).

Bumblebees with Kelsey

I’m spending my summer studying Bombus impatiens, or the impatient bumblebee, which is a common species in the Harvard Forest. This summer’s large experiment investigates how temporary food surpluses, or resource pulses, affect bumblebees when occurring at different points of the bees’ colony cycle. Colonies given an early resource pulse (like the typically early bloom of the forest canopy) could produce larger and more viable workers, and more queens at the end of the summer. I’m interested in how differences in size between bees of the same species, or even the same colonies, affect where bees are more likely to forage due to differences in flight energetics.

I’m spending my summer studying Bombus impatiens, or the impatient bumblebee, which is a common species in the Harvard Forest. This summer’s large experiment investigates how temporary food surpluses, or resource pulses, affect bumblebees when occurring at different points of the bees’ colony cycle. Colonies given an early resource pulse (like the typically early bloom of the forest canopy) could produce larger and more viable workers, and more queens at the end of the summer. I’m interested in how differences in size between bees of the same species, or even the same colonies, affect where bees are more likely to forage due to differences in flight energetics.

After a few weeks of prep, we have started the big resource pulse experiment. First, we mark the bees with colored paint pens so we can identify each bee by its hive and approximate life span.

Then, we set up clear tubes from our hives to these big structures, called hoophouses, which are full of flowers.

After pouring some sugar water down the tubes, we can observe bees flying through the tubes to their resources in the hoophouses and bringing pollen back to the hive. Last week was my first time seeing the bees hard at work, flying through the tubes!

Last week brought another exciting event when we also had Drew Faust, the President of Harvard University, visit the forest. She stopped by our field site to see the bees on her tour.

I’ve had a lot of fun learning to work with bees (especially because we’re three weeks in and I still haven’t gotten stung). I work with Dash everyday and he is starting to teach me how to identify the pollen we find on our bees.